The Harrying of the North early in the new year of 1070 was regionally a millennial event that caused as much social and economic change in Yorkshire and the North East as the Roman invasion a thousand years earlier or the Industrial Revolution seven hundred year later.

The North, physically isolated from the rest of England by the marshlands of the Humber and Mersey headwaters, had by the start of the second millennium evolved a unique Anglo-Scandinavian identity. East of the Pennines this was epitomised by the rump of the old kingdom of Northumbria which saw the Angle ‘House of Bamburgh’ vie for power and influence with Danish York. This situation had been resolved in the 1030s by intermarriage, and the lands north of the Humber enjoyed economic and political semi-independence from the English crown.

All changed in the 1060s when Edward 1 appointed Tostig, from the all-powerful House of Godwin, as Earl. Tostig’s imposition of harsh taxation was followed by a northern revolt. Tostig’s brother, the future King Harold, was forced to side with King Edward and Tostig was exiled. He returned a year later with King Harald Hardrada of Norway in an attempt to claim the English throne from his newly crowned brother, only to be defeated at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. King Harold, though, was subsequently killed at the Battle of Hastings, ushering in the new Norman age.

Northern unrest started immediately after the invasion. The Normans didn’t have a military presence in the North but, as elsewhere in England, they did impose a local Englishman to rule on the new King’s behalf. This was Copsig, who had been Tostig’s agent in the North, and was highly unpopular. He didn’t last long, barely two months. His attempt to subdue the House of Bamburgh by invading Northumberland resulted in his death.

Ultimately, Gospatrick of the House of Bamburgh bought the earldom. King William presumably wanted to buy into local support, as well as raise considerable funds to support his armies. Gospatrick is one of three of that name within the wider family. The first had been assassinated by Tostig a few years earlier. Earl Gospatrick was the grandson of Earl Uhtred of Northumberland and King Ethelred’s daughter Aelgifu and, through his father, the Cumbrian prince Maldred, was a great grandson of Malcolm 2nd of Scotland. The third Gospatrick was a major landholder across Yorkshire, including Richmondshire, and was one of a handful of the English nobility who survived and prospered under Norman domination.

In April 1068, the northern lords led a rebellion rather than tax their own people. It was a revolt against Norman tyranny, but was seen as a challenge for the crown and was the first in a series of uprisings that would culminate in the Harrying of 1070.

King William reacted quickly, subdued Mercia by force, built castles enroute north and at York, and the North yielded to him. Direct Norman rule was imposed through Robert fitz Richard. Although northern assets were seized, northern power was not destroyed.

In Jan 1069 Robert de Comines was appointed Earl and moved to impose control over Durham. He failed, was ambushed inside Durham, and was killed with most of his men.

This triggered a second rebellion by Earls Gospatrick and Maerlswein. They seized York and laid siege to the castle. The Yorkshire thegns, or local nobility, themselves predominantly of Danish extraction, rose in support.

The King reacted quickly, marched north, broke the siege, plundered York and built a second castle, controlling both banks of the River Ouse. The rebels were then forced into the dales from where they mounted an effective ‘hit and run’ campaign throughout the spring and summer of 1069.

Revolt turned to outright insurrection. King Swein of Denmark was encouraged, with Northern money, to take the English crown. The campaign was initially successful, destroying Norman power north of the Humber. The rebels, failing to understand how aggressive and mobile Norman warfare was, returned to their homes for the winter. The Danes, unable to maintain themselves within the ruins of York, moved to north Lincolnshire in October.

King William marched north, forcing the Danes back north of the Humber. The rebels managed to regroup and held the crossings through the Aire marshlands for three weeks until the Normans outflanked them, took York and bought an agreement with the Danes, who then left raiding the Northumbrian coast. The rebels again retired to the sanctuary of the hills, assuming that the Normans would hold York over the winter. King William held his Christmas court in York then acted to ensure that the North could never again sustain a Danish force or a rebel claim against his authority and crown. Taking the rebels and the northern communities by surprise, he harried the land from the Humber to the Tees in early 1070.

The harrying would appear to have been pre-planned, structured and coordinated, with a multi-pronged advance through the Vale of York, the Vale of Pickering and possibly into Holderness, into West Yorkshire north of the Aire marshes, and eventually across the Tees as far as Jarrow and the Tyne valley.

It is hard to say exactly what happened as there are no immediately contemporary Northern accounts of the harrying and the assessment of other accounts varies.

Orderic Vitalis, an Anglo-Norman monk writing fifty years after the event reported: “ To his shame, William made no effort to control his fury, punishing the innocent with the guilty. He ordered that crops and herds, tools and food be burned to ashes. More than 100,000 people perished of starvation. I have often praised William but I can say nothing good about this brutal slaughter. God will punish him.” Whilst Oderic Vitalis is generally historically accurate in his accounts, he is prone to exaggerate. For example, his account of the Norman invasion of 1066 quadrupled the size of Duke William’s fleet. I suggest that his account of 100,000 starving to death is also an exaggeration as it would be about 5% of the English population of that time, and the North of course survived and many of the old, pre-Norman, towns and villages survive to this day. I think that this is something we need to bear constantly in mind when assessing what the Harrying was.

John of Worcester, a contemporary monk who would have seen the refugees arriving in Worcester and listened to their tales, also reported: “ From the Humber to the Tees, William's men burnt whole villages and slaughtered the inhabitants. Food stores and livestock were destroyed so that anyone surviving the initial massacre would succumb to starvation over the winter. Some survivors were reduced to cannibalism. Refugees from the harrying are mentioned as far away as Worcestershire in the Evesham Abbey chronicle.” John reports that many, sadly, gorged themselves on food on arrival at Worcester Abbey and died almost immediately. His account is certainly credible. The dislocation of Northern society would have been immense…and their probably would have been cannibalism somewhere along their way.

I would like to explore where I think the reality lies. What is clear is that the Norman attack was constrained by: forces available, a short time span of two to three months, sustainability whilst harrying and the need to maintain a sustainable Norman occupation. The harrying certainly did result in the destruction of settlements, slaughter and destruction of grain and livestock resulting in destitution in the middle of winter, and the total dislocation of northern society.

Harrying is, and always has been, an accepted form of warfare – from the Romans to the present day. The Normans practiced it regularly when trying impose control or prevent uprisings in both England and in Normandy. In modern warfare, we will deliberately destroy enemy logistics, industry, energy sources and communication centres as a matter of priority. The burning of grain, slaughter of livestock, and the killing of those people who work the land was the medieval equivalent.

The reason the harrying was so severe is, I suggest, because it was in response to a rebellion against the crown.

The size of the Norman force and the manner in which they operated isn’t known but I suggest that small, coordinated groups of men, radiating out from York, would have destroyed crops and cattle and slaughtered men and women – but the limited force available to King William would not, I suggest, have had anywhere near total domination of the land.

Estimates of the size of the Norman Army in England vary considerably but current assumptions are that the Norman Army at Hastings was perhaps 7500 strong and that approximately 8000 Normans actually settled in England over the next couple of decades. Many of the Norman knights and men at arms were Breton and Flemish mercenaries, hence the constant demand for high taxes with which to pay them. But, given that the Normans had to garrison castles and control unrest in the South West, on the Welsh Marches and in East Anglia, even 5000 might be a generous estimate of the force available for the harrying.

What is known is that the harrying was most intense in parts of Yorkshire and dissipated as it moved north of the Tees, and that it created a deliberate famine. There was mass starvation and subsequent disease, with displaced populations. Refugees fled as far as Scotland, Cumbria and the Midlands. Exhausted peasants struggled to survive, with too many for the weakened economy to support. There were simply too few surviving domestic animals and farm implements. Many were forced into servitude. People sold themselves, into bondage, for food and there was considerable reallocation of complete estates from English to Norman lordship.

There are accounts of widespread banditry in what became the ‘Free Zone’ of the upland areas, as well as an expanded wolf population. Wolf hunting was a traditional sport for the English gentry, many of whom had been killed at Fulford in 1066 and in the subsequent unrest. By the spring of 1070 there was no one left to control the wolves, and refugees would have been an attractive source of food.

English society across Yorkshire and Durham was totally shattered and the effects within Yorkshire are evident in the Domesday Book of 1086. Durham, which was placed under the control of the Church, was not included in the Doomsday Book. King William achieved his aim - The North could never again threaten his control of England.

We can probably assess whereabouts the Normans did harry. In the 1970’s William Kapelle, in his book “The Norman Conquest of the North, The Region and its Transformation 1000-1135,” extrapolated research done by TAM Bishop in the 1930s. He looked at where the Doomsday Book recorded functioning churches and, hypothesising that functioning churches would only exist where there was a surviving peasant population, mapped out the probable route of destruction, with the presence of churches illustrating a continuity of population. The harrying would therefore appear to have most destructive along the Vale of York and into the Vale of Mowbray, north of the River Aire into the Pennines, and the along the Vale of Pickering into the northern Wolds.

Kapelle also analysed the distribution of over-stocked manors in 1086. Whilst some communities are shown in the Doomsday Book to be unproductive, others are shown as having more ploughs and therefore employed and sustained a larger population than before the harrying. This shows that not only did some manors survive but that their populations increased, possibly as a result of moving people from ravished manors in order to intensify production in the lands the Normans considered most favourable, more secure and where they had a strategic interest – such as Richmond.

The structure of the manorial estates changed. In pre-Norman times demesne land, that is land directly under the manorial lord’s control, was rare. By the time of the Doomsday Book the majority of manors had extensive demesne land indicating that land was taken from private ownership or custodianship, directly under the control of the lord of the manor, and through him, the King. The correlation of these manors with those with functioning churches is very close.

The Doomsday Book refers to villages with large tracts of waste land. This is often taken to mean that the land had been destroyed in the harrying, its inhabitants displaced and that it had lain empty since. Is that realistic? The villages’ names have endured through the centuries. This would not have happened if they had been destroyed and left uninhabited over several generations.

Villages, or manors, that are recorded in the Doomsday Book will have had some significance. Bearing in mind that the Doomsday Book was an accounting exercise to enable the King to identify how to tax his barons, I suggest that waste means that the villages were not generating a taxable income, probably surviving at a bare subsistence level because they held no significance to their overlord; but they did exist and merited recording in the national inventory of assets.

Kapelle proposes that one reason that the Normans were less interested in the marginal lands is that, for social reasons, they would only eat bread made from wheat. There are accounts of Norman overlords giving up their estates because they could not feed their families on wheat bread. Bread made from Rye, Oats or Barley was considered too socially unacceptable.

Medieval wheat would not grow in cool damp climates, and land over 400’ was found to be too marginal for its cultivation. This situation actually persisted until the early 12th Century when Henry 1st used less socially-picky knights from Brittany and Maine to settle Cumberland, Northumberland, Dumfries and Lothian. This could be one reason why the land of many upland villages was taken out of production and declared waste.

When looking at the Doomsday Book, comparison of the population densities of Yorkshire and the shires immediately to the south shows the impact of the harrying. Population densities in Nottinghamshire and North Lincolnshire are approximately double those in Yorkshire.

The number of plough teams (usually eight oxen) also bears looking at. There are two to three times more in Nottinghamshire and North Lincolnshire, but the number of plough teams is also higher in parts of Yorkshire including Richmondshire, south of York, and south of the River Aire.

The demography of Yorkshire would certainly have changed. It is probable that the young who were productive and valued, survived; whereas the elderly and infirm were left to starve. Population was higher where there was a strategic interest such as castles, communication and entry routes, and wheat production. Communities were probably moved from upland to lowland areas, though marginalised upland communities survived.

In summary, the Doomsday Book shows that sufficient people survived the harrying to ensure that the Normans could sustain themselves across Yorkshire and Durham and ensure that the people could not rise against them, or that the land could support a further Danish invasion.

Some English lords did retain their lands, and gain further ones, but only as an under lord. The third Gospatrick is an example.

Those that did survive did so in a very different social environment. Freemen, including those with minimal landholdings had largely disappeared. In 1066, there were more freemen in Northallerton and Scarborough (224) than the whole North and East Ridings in 1086. In 1086, there were three times as many freemen in Nottinghamshire as in Yorkshire.

Most social classes were replaced by a disproportionate number of villeins, with 80% of the Yorkshire population classed as such. Villeins were a class of feudal serfs who held the legal status of freemen in their dealings with all people except their lord. Holding a small amount of land from which to sustain their family they typically owed two days’ work a week to their lord and six days a week during the 5 weeks of the harvest. This was the most efficient means of exploiting free labour.

Although overall productivity was significantly lower by 1086, estates in the key areas were more productive, reflecting how the Normans directed the people’s work to their will. With a significant increase in demesne land retained for the manorial lord’s own use.

We can see that The Doomsday Book indicates that the intensity of the harrying varied. It is quite likely that the Normans had decided in advance which were the strategically important areas that they wanted to settle in, and from where they would exercise control. These would not have been harried to the same extent as those areas of low importance, which could be destroyed to set a very clear example of Norman domination.

There were other changes too, some were imposed in order to further constrain English freedoms, others were consequential. The church became more Norman Catholic, being forced away from traditional English Orthodoxy and denying priests the freedom to marry. The use of written English was forbidden thereby depriving the English of the ability to communicate, other than verbally, as very few knew Latin. This meant that the English really were the new underclass.

Norman domination of the lowland areas resulted in significant banditry in the uncontrolled upland zones. This enabled a resistance to develop. As Peter Rex explains in his book “The English Resistance – The Underground War against the Normans,” the 1070s is analogous to wartime France, with a fractured but organised resistance. The difference was that in the 1940s the French resisted in the increasing hope of the arrival of an army of liberation. As the hope of a Danish Army of liberation faded in the 1070s, so the will and ability to rebel or resist the Normans faded.

The initial resistance was considerable. The upland areas were known as a free-zone, the habitat of outlaws. The Normans called them the Silvatici – the men of the woods. We perhaps know them better as the Green Men, or Robin Hood and his Merry Men. Simeon of Durham, a contemporary chronicler and monk of Durham Priory, reports that throughout the 1070s travel across the empty countryside that separated Durham and York was extremely dangerous on account of outlaws and wolves.

Other accounts support this. The founders of Selby Abbey were harassed by outlaws who lived in the woods in the 1070s and Hufh fitz Baldric, the Sherriff of Yorkshire, is said to have had to travel around the shire with a small army because hostile Anglo-Saxons were still at large. Even the monks at Whitby were so troubled that as late as the reign of William 2nd they tried to settle elsewhere.

To help protect the conquerors from being murdered by the English, King William introduced a new law known as the ‘Murdrum’ or, more probably, reintroduced an earlier law imposed by King Cnut for the murder of Danes. Marc Morris writes in ‘The Norman Conquest’: “By this law if a Norman was found murdered, the onus was placed on the lord of the murderer to produce him within five days or face a ruinous fine. If the culprit remained at large despite his lord’s financial ruin, the penalty was simply transferred to the local community as a whole, and levied until such time as the murderer was produced”. This was a strong incentive to submit rather than resist. The safe haven of the resistance – The Greenwood – was also closed off as a sanctuary by the Forest Laws.

Laws were one of the hallmarks of the feudal system that King William imposed on England after 1066. The Forest Laws applied not just to woods, but also heath, moorland and wetlands superseding the earlier Anglo-Saxon laws in which rights to the forest were not exclusive to the king or nobles, but were shared among the people. The Norman laws were harsh, forbidding not only the hunting of game in the forest, but even the cutting of wood or the collection of fallen timber, berries, or anything growing within the forest. The punishments for breaking these laws were severe and ranged from fines to, in the most severe cases, death. Because of these forest laws the local peasants who lived on the land faced severe restrictions on their lifestyles. As the ‘underwood’ was protected they faced a severe restriction on their ability to gather wood for fuel. The risk for any resistance operating from the forest was significant.

Richmond itself isn’t mentioned in the Doomsday Book, but two manors are. One is called Hindrelag. This is possibly the original English settlement, which may have been located in the vicinity of St Mary’s Church or immediately above on Anchorage Hill. The other was ‘Neutone’. This was possibly a new settlement and in ‘The History of Richmond’, Jane Hatcher suggests that it was built outside the bailey wall of the new castle of Richemund, possibly where Newbiggin now is.

The land around Richmond was granted to William’s relative, Count Alan Rufus of Brittany, who was one of the most powerful amongst the Norman nobility. Count Alan focused on building one of the county’s first stone castles at Richmond, which was known as ‘the strong hill’ in Norman French. It was to be the Norman’s centre for their regional control, replacing Gilling West which had previously been the regional centre. Building started in 1071, perhaps indicating that the harrying had been strategically planned.

Richmond would have been established as a strategic hub on the new northern border, controlling communication links and food production, and enforcing a barrier between the fertile valleys and the inhospitable and dangerous free-zone of the upland dales.

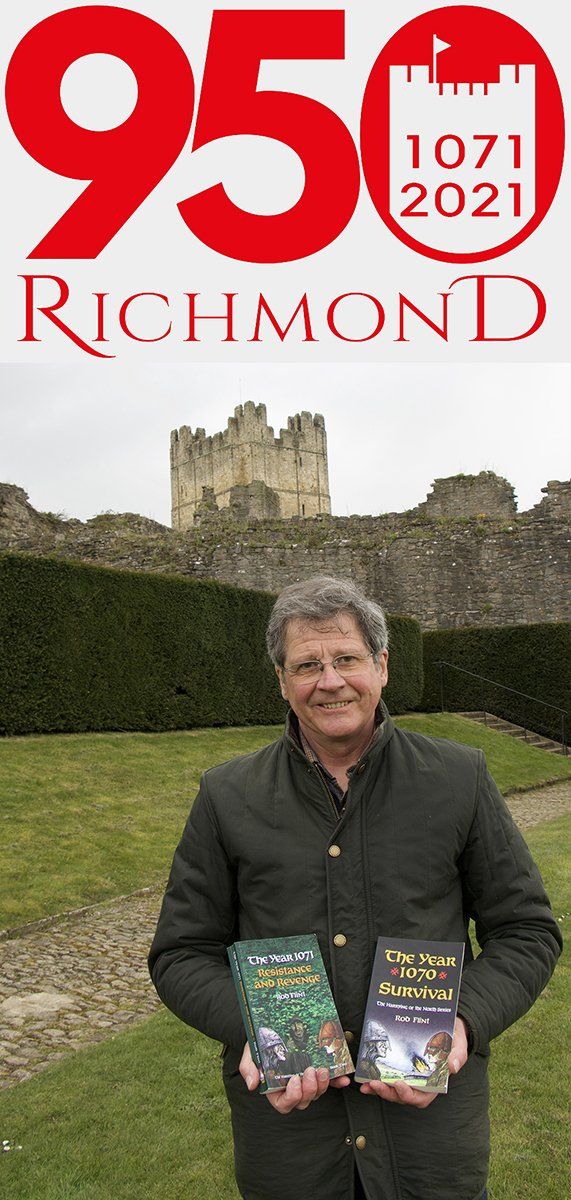

Their ISBN numbers are:

The Year 1070 - Survival: 978-1-9999893-0-9

The Year 1071- Resistance and Revenge: 978-1-9999893-1-6

My local stockist is:

Castle Hill Bookshop

1B Castle Hill

Richmond

North Yorkshire

DL10 4QP

01748 824 243

www.castlehillbookshop.co.uk